Plain Talk Series on Understanding Voting System Updates Part 2: The Physical Purchase

Eddie Perez

This is the 2nd of a 6-part series of slightly longer vignettes on the challenge of updating voting systems. It’s a slice-and-dice of a recent briefing on the topic.

It’s intended to acquaint relatively newcomers to understanding how voting system are purchased and maintained, and that includes anyone and everyone from concerned citizens, to journalists, to policy makers.

Purchasing a Voting System

When states, counties, or townships purchase a new voting system, the transaction usually involves two different “buckets” of cost – some at the time of initial purchase, and some of it spread out over several years, through annual fees for “support and maintenance.”

In this post, we’ll begin with the first of those two: the tangible “things” or physical products that election jurisdictions typically pay for at the time of the initial purchase: the voting system components that are delivered to a warehouse.

Voting systems include a combination of hardware and software. Hardware typically includes:

- Desktop computers, which back-office election staff use to design elections and tabulate votes;

- The voting devices themselves, (e.g., ballot scanners, ballot marking devices, or other digital machinery for in-person voting; and in some cases

- High-speed scanners for jurisdictions with a lot of by-mail voting.

In addition to the hardware, every piece of equipment also includes:

- Software that allows it to perform its functions; the installed software is a combination of “commercial-off-the-shelf” (COTS) software designed for “mainstream,” non-voting specific applications (e.g., Microsoft operating systems (OS) are common), plus

- Additional proprietary software (commonly called the “election management system,” or EMS), which the voting system manufacturer develops and integrates with the operating system.

A common question: “Is software included in the price?”

It’s important to note that when an election jurisdiction takes delivery of voting system hardware and software, it typically “owns” only the hardware itself. The jurisdiction does not “own” the software installed on the devices, however; instead, it has a “right to use” the software, which is granted through payment of a “license” for each instance of the software installed.

For example, in addition to the cost of a computer, a back-office EMS desktop PC may include the cost of an operating system license, plus a license to use the vendor’s ballot design or tabulation software, which is also installed on the PC; and each voting device would also require a license for its installed software, in addition to the cost of the device itself.

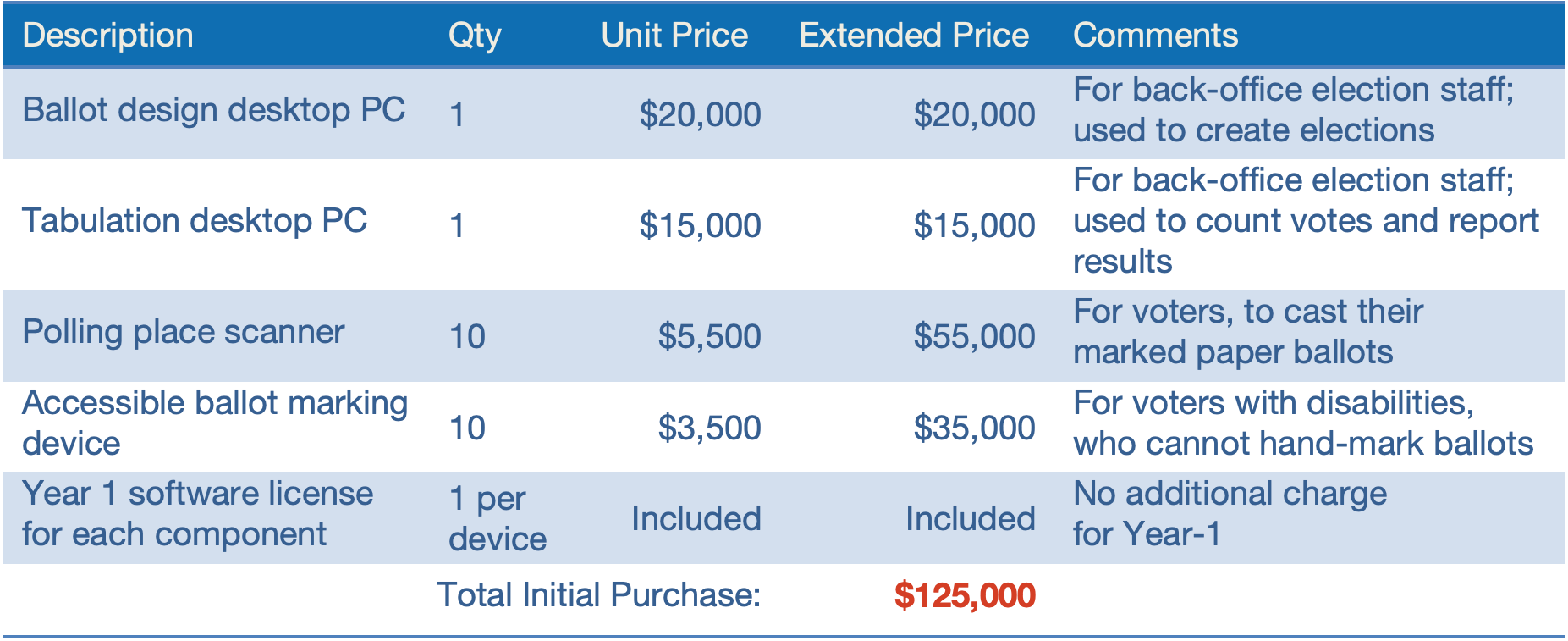

A Typical Voting Systems Bill

To illustrate a simplified “bill of sale” for a new voting system purchase, it might include the following hardware and software (among other things):

Another common question: “Why does the distinction between hardware and software matter?”

The fact that election jurisdictions have only a “right to use” software through payment of a license – but they do not “own” the software – means that they although they take ownership of election devices, they must continue paying fees, year after year (for a long as their contract with the voting system vendor lasts), to continue using the software installed on the voting components they own.

Those fees lead us to our 2nd type of cost item associated with a voting system purchase: Annual Fees.

Those are the topic of the next blog in our series.To read more, here are all of the articles in this Voting Systems Update Series published to date.