Explainer: The Facts About By-Mail Ballot Security

Eddie Perez

Introduction

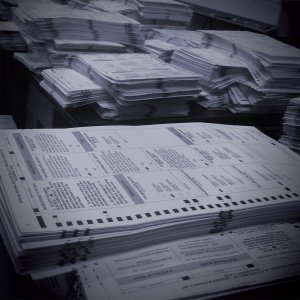

With Election Day (November 5) for the U.S. Presidential Election approaching, we anticipate that the coming weeks are likely to launch a new cycle of disinformation intended to undermine public confidence in the legitimacy of election outcomes. We have referred to these efforts as “manufactured chaos:” coordinated efforts to interfere with — and potentially overwhelm — normal election administration processes (including procedures and/or technology), based on assumptions of irregularities or malfeasance, even when allegations are not supported by facts. As part of the chaos that’s likely to come, we anticipate that false narratives around by-mail ballots in particular are likely to be one of the key themes, just as they were in 2020. Since then, despite the fact that inaccurate and sensational claims about by-mail ballots have been thoroughly and repeatedly debunked, they remain one of the most widespread forms of disinformation. These assertions need to be thoroughly clarified and corrected, because they are not based on facts.

In this Explainer, we dig more deeply into the details of by-mail voting operations, as well as the technical features associated with creating and printing ballots. Through a series of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), we show that “fake” by-mail ballots cannot be simply “dropped into” an election, or into drop-boxes, willy-nilly, as some inflammatory assertions would have you believe.

The facts are that outbound mailing of blank ballots, inbound return of voted ballots, and scanning and tabulation are all tightly controlled. More specifically:

- Blank ballots are not simply sent out “en masse,” without controls;

- By-mail voting depends on well-vetted records to determine voter eligibility, just like in-person voting;

- Returned ballots undergo a rigorous verification process, to ensure that they are valid; and

- Technical features of ballots make it difficult for a bad actor to copy them without detection —sort of similar to counterfeiting money, but not as complicated; yet, still difficult and so far, without the same level of criminal liability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Isn’t by-mail voting a “tidal wave”?

Answer: No. Despite what some would have you believe, there have been no efforts to impose “nationwide” by-mail voting, in the sense that millions of ballots are being proactively sent to people everywhere. In fact, the U.S. doesn’t have a uniform national election system; instead, in accordance with the Tenth Amendment, each individual state decides how to administer its own elections, so it’s up to each state to decide whether to offer by-mail voting, and exactly how it will be implemented (because there are different ways of doing it, as we see below).

Doesn’t by-mail voting favor one party over another?

Answer: No. By-mail voting has broad bipartisan support, and it is not “new.” In fact, for many years, every single state has had provisions to offer by-mail ballots to certain voters instead of voting in-person, and by-mail voting has been successfully used for military and overseas voters for decades. Broadly speaking, the protocols and security associated with by-mail ballots have been tested again and again, for years. Furthermore, in recent years, Republican and Democratic states alike have greatly expanded access to by-mail voting. The trend is strongly bipartisan, and no-excuse mail voting options (i.e., available to all registered voters, without needing to provide an “excuse” for not voting in-person) are available in states with red and blue governors alike. Furthermore, recent research from Stanford University found that by-mail voting is neutral in its partisan effects, in terms of both turnout and outcomes.

With by-mail voting, isn’t there mass mailing of ballots to all manner of people?

Answer: No. With by-mail voting, the issuance of blank ballots is highly controlled. By-mail voting issues blank ballots only to registered voters, just like in-person voting. More specifically, election officials match voter registration records to individual blank ballots before any are sent through the U.S. Postal Service (USPS). And, when voters return marked ballots to the elections office, there are strict verification protocols in place (see below for details).

With by-mail voting, don’t all voters get a blank ballot?

Answer: No. Only eight states (CA, CO, HI, NV, OR, VT, WA, UT) and the District of Columbia proactively send blank ballots to all registered voters. The vast majority of states are requiring voters to submit a mail ballot request before the elections office will issue a blank ballot to the voter (and the request and the voter registration record are, of course, tracked by the elections office). With by-mail voting, states continue to implement all of their state-specific rules to determine eligibility and to maintain integrity, including the need for IDs, signatures (under penalty of felony crime), and other forms of voter qualification. In short, elections offices know exactly who is issued a blank ballot, and how many ballots the office can expect to receive in return.

As a result, since every single ballot issued is tied to a specific voter registration record, for a malicious third party to “counterfeit” a ballot, they would need to know personal voter information, to “mimic” the real voter – and they would also need to return the voted counterfeit ballot at exactly the right time, (i.e., before the real voter – assuming that the bad actor could somehow know or verify that that individual voter had indeed requested a ballot, or was supposed to receive one). But that’s just the beginning.

Can’t someone simply create fake ballots? Isn’t it just a bunch of titles, names & ovals?

Answer: No. For a long list of reasons associated with the complexity of election data, voting system software, and printing specifications, creating a counterfeit ballot that evades detection is difficult.

First of all, to be accepted as a valid ballot by voting system scanners, ballots must be created with specialized software from the voting system; only that software can create a properly-formatted layout that the voting system will accept.

More specifically, for a ballot to be accepted by the voting system as valid, a counterfeiter would need to know all of the following technical specifications:

- Codes that uniquely identify the specific election

- Precinct codes associated with sub-units of the election jurisdiction

- Specific election content

- A variety of additional validation information, such as “checksums,” which are typically encoded in barcodes.

In other words, when ballots are scanned, the voting system will only recognize ballots that were programmed from the voting system itself, through the use of specialized software that is secured in the elections back-office, as part of the “election management system.” Some of the validation that the scanners are looking for isn’t even human-readable; sometimes, it’s invisible to the eye, in a barcode; or it may be a handful of numbers, devoid of context or meaning to the casual observer.

And finally, another reason that it’s hard for a bad actor to counterfeit ballots is because of different “ballot styles.” In other words, in a given election, not all voters have ballots that look the same, due to cross-cutting Federal, State, and other district boundaries (which vary by address). As a result, an election could have dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of distinct ballot styles, each of which must be validated by the voting system software — and a bad actor would need to get them exactly right.

What’s so hard about printing a bunch of ballots? Isn’t it like using a copier?

Answer: No. Ballots must be printed to exacting specifications in order to be accepted by voting system scanners. It’s not like making copies on office-grade photocopy paper. In addition to all of the election data and ballot logic that a bad actor would need to get right (see above), ballots and scanners require:

- specific paper weights;

- exact margins;

- exact image sizes; and

- exact placement of option boxes or ovals.

If any of those printing specifications are incorrect, the scanner will reject the ballot, thereby alerting election officials of any ballots that require further investigation.

What’s to prevent a fake ballot sent to the elections office from being accepted?

Answer: Assuming a bad actor could jump through all the difficult technical and printing hoops we’ve described above to make a “fake” or counterfeit ballot, when it’s received at the elections office, the envelope containing the ballot in its own secrecy envelope is validated with a barcode uniquely tied to a voter registration record.

So, every incoming piece of mail is being checked for three things:

- Does it have a barcode in the specific format that the elections office uses?

- Does the barcode on the envelope link to a valid voter registration record; and

- Was a ballot actually mailed to that voter?

What’s to prevent someone from returning a ballot intended for a different eligible voter?

Answer: The voter’s signature. Ballots inside returned envelopes aren’t accepted for counting until the voter’s signature on the outer envelope is validated by authorized people – usually bipartisan teams.

Signature verification is a critical part of ensuring that only valid ballots from eligible voters get counted. In fact, some larger jurisdictions even train their elections staff and bipartisan teams on handwriting analysis from forensic experts associated with the FBI, for example. If a ballot return envelope is missing a signature, or if the signature does not appear to match the one on file, some states have a process to address or “cure” these discrepancies by notifying the voter on the address of record there is a concern about the signature and allowing them to provide their signature again – but sadly, many states do not offer such an option to voters. Signature curing (where offered) ensures ballots from eligible voters can be counted – and conversely, since a bad actor would be unlikely to respond to inquiries about signature discrepancies, counterfeit ballots would be rejected, and never counted.

Note: As mentioned above, not all states enable a voter to “cure” a signature mismatch; some states simply perform a “signature reject” and they may not even notify a voter to let them know their ballot was rejected.

When counting votes, isn’t it possible to “dump” large volumes of fake mail ballots at the counting center in the middle of the night, to change the outcomes?

Answer: No. The false idea that key jurisdictions “stopped the election in the middle of the night” in 2020 to “fix” the results is one of the more pernicious falsehoods that continues to this day. The claims are false for two reasons. First, it simply takes time to process and tabulate mail ballots. Unlike in-person voting, thousands of ballots must be removed from envelopes; each ballot must be cross-checked with voter registration data; and signatures must be verified before the ballot can even be accepted and scanned.

Furthermore, the delay in processing is exacerbated in some key states because some are prohibited from processing mail ballots before Election Day. In critical states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, officials are not allowed to even begin processing by-mail ballots until polls open on Election Day.

Thus, in states where preprocessing is not allowed, it creates a bottleneck, which means that there is no other option but to report mail-ballot results after the polls close on Election Day, perhaps in the middle of the night. And in states with large numbers of by-mail ballots, it may take several days to complete the scanning process.

It’s also important to note that modern voting technology can contribute to the appearance of sudden “spikes” in ballot counts. Modern ballot scanning systems typically allow election officials to scan and store cast vote record data for thousands of mail ballots before actually tabulating the results on Election Night. For example, states may spend weeks preprocessing and scanning thousands of ballots, day after day, and the cast vote record data is “held” or stored on a memory card until Election Night. The results are not aggregated and reported until the memory card is inserted into a tabulation computer after the close of polls on Election Day — at which point results from those ballots suddenly “appear,” all at once. But those are not “ballot dumps;” the appearance of results from many ballots all at once is an artifact of reading the memory card at a distinct point in time, even if the memory card reflects prior ballot scanning that has taken weeks to complete.

Finally, it’s important to remember that for all of the security and validation reasons described above, it would also be an enormous effort to insert thousands of “fake” ballots into the work-stream without detection; there are simply too many security features and cross-checks that would have to be overcome.

Review & Summary

To summarize, all of the following aspects of by-mail voting have a host of security protocols and safeguards:

- Outbound mailing of blank ballots

- Inbound validation of voted ballots

- Processing and scanning of voted ballots

Here are the details…

The outbound issuance of blank ballots is controlled:

- Ballots are not sent “en masse”

- Ballots are not sent to “just anyone”

- Ballots are usually not sent proactively

- Ballots are tied to validated records of eligible voters

If a returned ballot cannot be associated with an eligible voter, it’s investigated.

The inbound validation of returned ballots is controlled:

- Returned envelopes are barcoded in a specific format

- Returned envelopes are verified against voter registration records

- Returned ballots are verified against records of ballots mailed

- Returned envelopes are typically verified by comparing signatures to those on file

If a returned ballot fails any of these, it’s investigated.

The processing and scanning of marked ballots is controlled:

- Ballots must meet all technical specifications of voting system software

- Ballots must conform with all data logic contained in the specific election definition

- Ballots must meet all printing specifications

If a returned ballot fails any of these, it will be rejected by the scanner.

And last but not least, please do not listen to, read, or take as truth the inflammatory talk or content about “fraud” associated with by-mail voting. It’s just talk, and the facts say otherwise. Documented rates of fraud associated with by-mail voting are incredibly small.

Conclusion

The OSET Institute hopes that this Explainer puts to rest some of the irresponsible claims that have been made about the security of by-mail voting. By-mail voting continues to be an essential part of providing access to the ballot box during the November 2024 Presidential Election, along with a proper balance of in-person voting locations for those who want or need to vote that way.